War banished, development began. The old Stanegate [A Roman road] along the Roman Wall gave place to Wade's military road - a road which brought qualms to the protectionist spirit of the guildsmen, which gradually but surely, however, gave way before the spirit of free trade set up from the east. This trade was extended by the opening of the Canal in 1823, and then, much more rapidly, by the opening of the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway in 1835, these "highways of commerce" making it possible to import cheaper coal and proceed with the erection of factories.

EARLIEST MANUFACTURES, 1745-1800

In his "Worthies of Cumberland," written in 1662, Fuller records the manufacture, commenced two years previously, of "fustians" - roughly twilled cotton goods of the corduroy type - but this, apparently, did not continue long, for there is no further reference to it. In these early days the fish-hook trade, still with us, was not very lucrative, for the half-dozen persons then engaged in it are designated by one writer as "paupers"; nor would the whip-business be on a scale much more extensive, the greater part of this latter work being executed by children.

Hutchinson was in close touch with Carlisle during the latter half of the eighteenth century, and his review of the city's trade during that period is as interesting as it was comprehensive

"Before this time day labour for men not brought up to any mechanical trade, with lint or tow spinning for example, was all the employment which could be obtained. Eightpence or tenpence a day was as much as a labourer could earn, and a woman must have worked very hard at her wheel to make a shilling a week. The employment for children was winding pirns [bobbins] for weavers or twisting whips, for which they had only about eightpence per week and generally worked sixteen hours out of twenty-four.

"The establishment of the calico manufactory (1761) greatly altered the case. The work in the green or bleaching yard found employment for men or stout boys. Apprentices were taken to the several branches of the work at a genteel allowance, and their wages increased as they advanced in their servitude" (a word richly suggestive). "Little boys were employed as tearing boys to the printers. Women had tables set out for them to pencil the colours into the pieces. Every table employed three or four female children; and even the youngest boys and girls could make near two shillings a week. Such encouragement brought numbers of families out of the country into the city and suburbs, and so great was the change that a common labourer, who probably with his wife's assistance did not previously make above eight shillings weekly, could, by having his family fixed in the manner represented, easily earn twenty or thirty shillings a week."

"The several manufactories began to thrive much beyond the most sanguine expectations. People in trade, with little to begin with, acquired fortunes which enabled them to live in a much more splendid style than formerly. The town rapidly improved, and the land around increased in value far beyond what could have been foreseen."

"The advantages, however, were balanced by some inconveniences: people of property who tasted not the sweets of a thriving trade began to feel the disadvantages which arose from the increase of population. Before the year 1761 the poor rates were not felt by those who paid them; but the increase of manufactories invited numbers of strangers here for bread. The town was soon filled with Scotch and Irish families; and as these people had no place to return to in case of indigence and sickness, they became a great burden upon the ancient inhabitants."

AN EARLY WOOLLEN FACTORY: OSNABURGS

Before the introduction of calico-printing, however, in fact, very soon after 1745, a woollen business was introduced into the town by a company of merchants from the German port of Hamburg. Two brothers, Deulicher by name, were placed in charge, and for a considerable time the business flourished. Then the elder brother, the chief manager died, and the younger was quickly brought to grief by the machinations of a foolish, ambitious, and in more ways than one, a highly expensive wife. At her instigation the older workmen, who had been acting as overseers, were supplanted by her less businesslike friends; troubles with the workers almost immediately followed; and the result was ruin in the shape of bankruptcy. Other adventurers endeavoured to resurrect the trade, all their ventures, however, ending in collapse.

Another early business connected with Germany was that of the manufacture of Osnaburgs - coarse linen cloths, so called from the German town where they were first manufactured. A business was initiated in 1750 by Aldermen Richard and William Hodgson, the new road offering facilities for the import of flax from Hamburg. But four years before this date, when the troubles of the "Forty-Five" had barely subsided, a similar business had been set up below the Town Hall by Richard Ferguson, who found his raw material, coarse linen yarn, exposed in the city's market place for sale by traders from over the Border. His "checked goods" almost immediately found favour, and the business flourished exceedingly.

CARLISLE'S ONCE STAPLE INDUSTRY

In pointing out the excellent qualities of Carlisle's waters, especially those of the Caldew for bleaching purposes, Hutchinson remarked "that it was rather an unpleasant reflection that these rapid streams, so peculiarly adapted to the turning of machinery for miles above Carlisle ..... should only be employed in giving motion to three or four solitary corn mills and a few cotton works"; proving himself at the time a true prophet, for his prophecy was based upon accurate observation, by suggesting that "the city might easily be rendered the Birmingham of the North." To a very material extent that forecast has been realised, since today Carlisle is certainly one of the most important, if not the principal manufacturing town between Lancashire and Glasgow.

That prophecy, too, was not without immediate effect; the cotton trade, from that time and half a century onwards, developing to a degree extraordinary.

So successful was the calico-printing business, established in 1761 by Scott, Lamb and Co., of Newcastle, that by 1796 this neighbourhood boasted no fewer than four "print-fields," as they were termed - Messrs. Lamb, Scott, Forster and Co.; Losh and Co.; Mitchell, Ellwood and Co.; and Donald, Carrick, Shaw and Co. It was quickly realised that these businesses would benefit financially if their raw material, calico, could be manufactured in this district, to avoid the cost of transporting it from Lancashire. Three of Richard Ferguson's sons had already in 1791 opened a cotton factory at Warwick[4], but family reasons made it necessary to procure further assistance to carry on the Fergusons' various concerns, and this was fortunately forthcoming from a relative, Mr. Peter Dixon, a merchant of Whitehaven, and his two sons, John and Peter.

THE DIXON FAMILY

This family removed to Carlisle in 1812, and in a few years the name of Dixon - still highly honoured in both City and County - was one to conjure with in Carlisle. The business went rapidly ahead under the name of Peter Dixon and Sons - a firm which was to be one of the mainstays of the city till 1883, when their business, for various reasons, came to an end.

The name Dixon is one familiar to every citizen of Carlisle, the "Dixon's Chimney" is a landmark for miles around the city. It was erected along with their extensive factory in Shaddongate in 1835-36, and, towering to a height of 305 feet, has an internal diameter at the base of 17 feet 8 inches, the walls there being 10 feet thick. The factory is 124 feet long, 58 feet wide, and 83 feet high, and it is still one of the delights of passing children to count its 351 windows. When it is remembered that in addition to this building the firm had warehouses and other departments in Peter Street, Tait Street, and at Warwick, some conception may be formed of the extensive ramifications of the business for which it was once responsible.

The rapid development of the cotton trade in a town, which, fifty to sixty years before, was practically without manufactures, may he further estimated from some figures given in a directory of 1847. Then Messrs. Peter Dixon and Sons found employment for no fewer then 8000 hands; and besides four huge spinning mills in Carlisle, there were two at Dalston, one at Warwick Bridge, and another at Cummersdale, containing, collectively, about 122,000 spindles. There were also in the city and its vicinity eight manufactories producing ginghams (cotton cloths made of dyed yarns), checks, shawls, and other kindred materials; several bleaching and finishing establishments; and, at Cummersdale, the nucleus of the present calico-printing works of Messrs. Stead, Mc.Alpin, producing goods which have earned a name recognised as a synonym for excellence in every corner of the globe.

Other respected names once associated with this staple trade of Old Carlisle are those of Slater (Water Street), Donald (Denton Hill), Story ("Beetlers" in Shaddongate and Denton Holme), and Dalton (Cummersdale).

THE COTTON DECLINE

In the sixties the American War between North and South played sad havoc with the cotton trade in this city and throughout Lancashire. The stopping of the export of raw cotton from the United States practically brought the English manufacture of cotton goods to a standstill, causing intense suffering among the workers. Trade revived in Lancashire with the cessation of hostilities, but Carlisle never recovered, for - but let Bulmer tell that story:

"The golden days of the cotton trade in Carlisle fell with the abolition of slavery in America. Formerly every great slave plantation look a large quantity of gingham for its negroes, and always adhered to the same patterns. Thus, when other orders were dull, the Carlisle spinners worked on for the American trade, sure of their annual orders. But the free negro demands a gaudier article; he is capricious, and must be tickled and attracted by new patterns. This altered state of things the Carlisle spinners have, from various causes, been unable to adapt themselves to, and it seems probable (the directory is dated 1884) that the trade will shortly leave Carlisle, and that its streets will cease, as in great part they have already done, to re-echo to the clattering clogs of countless mill-girls going to and from their work."

THE FERGUSONS AND HOLME HEAD

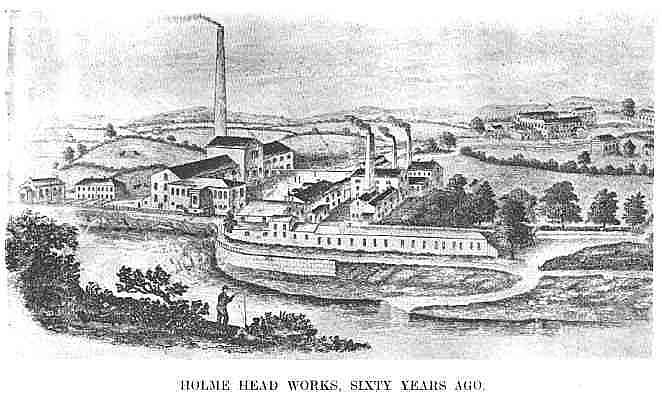

The Dixons, as manufacturers, have gone, but the enterprise of the Fergusons is still in evidence at the ever-extending works at Holme Head, where business is flourishing today despite the almost general "slump" in trade which followed the war. Here there is palpable proof that real success in business can best be assured by co-ordination of effort between masters and men. When this truth is grasped and acted upon, as at Holme Head, there will be little or no fear of "national decadence in respect of our long held position of supremacy at the head of the world's commerce."

Mr. Joseph Ferguson, the founder of the works in 1825, was the

grandson of Mr. Richard Ferguson, who, as already stated, commenced business in the Market

Place about the time of the "Forty-Five." In 1836-37 he was Mayor of Carlisle,

and subsequently (1852-57) represented the City in the House of Commons. His son, Mr.

Robert Ferguson was twice Mayor, and also M.P. for Carlisle, 1874-1886. Mr. Robert

Ferguson's sister, Maria Isabella, married Mr. Edward Chance, of Birmingham, and two of

their three sons, Mr. F. W. (now Sir Frederick) Chance and Mr. J. Selby Chance, have for

almost half a century taken a leading part, not only in the development of the business,

but in almost every movement, municipal and parliamentary, calculated to benefit the City

of Carlisle and the county of Cumberland.

Mr. Joseph Ferguson, the founder of the works in 1825, was the

grandson of Mr. Richard Ferguson, who, as already stated, commenced business in the Market

Place about the time of the "Forty-Five." In 1836-37 he was Mayor of Carlisle,

and subsequently (1852-57) represented the City in the House of Commons. His son, Mr.

Robert Ferguson was twice Mayor, and also M.P. for Carlisle, 1874-1886. Mr. Robert

Ferguson's sister, Maria Isabella, married Mr. Edward Chance, of Birmingham, and two of

their three sons, Mr. F. W. (now Sir Frederick) Chance and Mr. J. Selby Chance, have for

almost half a century taken a leading part, not only in the development of the business,

but in almost every movement, municipal and parliamentary, calculated to benefit the City

of Carlisle and the county of Cumberland.

Examples of the work done at Holme Head have found their way to leading exhibitions both at home and abroad, and (to quote from the "Journal" of October 21st, 1913) "the wording of the award granted to the firm by the United States Centennial Commission for the International Exhibition at Philadelphia, 1870, sums up the outstanding features of their products today: 'Fineness of texture, superior colours, superb dyeing, with a finish of remarkable excellence. The harmony and blending of colours is exceedingly fine, also in great variety.'"

Work deserving such praise will hold its own without fear of world-wide rivalry. [The above image dates from about 1860.]

CARLISLE'S HAND-LOOM WEAVERS - A LIFE OF PENURY AND TOIL

Among the many interesting documents and old records we have perused in quest of the "Memories of Old Carlisle" none has appealed more forcibly than the "Autobiography of William Farish." This unique book, a well written (perhaps egotistical and garrulous, but always lively) record of the life of the handloom weavers of Caldewgate, gives, first-hand, the impressions and experiences of one of them.

THE WEAVERS' WORKSHOPS

In the early days of the 19th century when cotton was the staple industry of the North, hand-loom weaving was a thriving and profitable occupation in Carlisle and the surrounding villages. Indeed, the most familiar sounds to be heard within a radius of twenty miles or more around Carlisle were the whirr of the bobbin-wheel and the buzz and click of the shuttle. At that time the average weekly wage of a common labourer in this district was eight shillings; a weaver, however, assisted by his wife and family, could earn over twenty shillings a week. Thus, hand-loom weaving being a labour in which women and children, as well as men could engage, and one which could be carried on at home, with emoluments comparatively generous, many families adopted this occupation. Looms were set up in the kitchens of many cottages; or a room was devoted entirely to the looms at which father, mother and children worked. In other cases, squads of two, three, or even six men would rent a room on the ground floor of a tenement, and, fixing up their apparatus, establish there a weaving shop, their product being delivered weekly to Messrs. Dixon at their Peter Street warehouse.

THE LAST OF THE CRAFTSMEN

Practically the whole of Duke Street and Back Duke Street [directly opposite Dixon's chimney] - the latter familiarly known in the old days as "The Ball-Alley" - consisted of weaving shops on the ground floor, with living rooms above. We distinctly remember, within the last thirty years, watching the one or two old hand-loom weavers who still continued to ply their skill at this dying industry. The cloth woven was in "check" pattern, and was utilised for the making of aprons. One at the last of the craftsmen was Joseph Routledge, who, even within the last decade [meaning the 1910's], followed his craft in a shop in Rigg Street, where he produced cloth suitable for underskirts.

WILLIAM FARISH

The parents of William Farish were both hand-loom weavers. His father, of Irish birth but Scottish extraction, having migrated from Armagh in pursuit of his occupation, finally settled, like many other Irishmen, in Carlisle. His mother was a daughter of William Hall, who occupied his own patch of freehold, Moss Nook, in the parish of Hayton, where the descendants of this family still reside. This couple began their married life in one of a row of thatched cottages in Church Street, Caldewgate, the site of which has since been absorbed in the works of Messrs. Carr and Co. From this cottage they shortly afterwards removed to a large room over a six-loom weaving shop, in a yard in Caldcoats, the property of James Mc.Cutcheon, and here William, the author of "The Struggles of a Hand-loom Weaver," was born in the year 1818.

THE POVERTY OF THE LOOM

Unfortunately, the prosperity of the industry was short-lived. Even in its best days it was subject to depressions that bore hardly upon its employees, these being most acutely felt in those homes - the majority - where the whole family followed the loom. At such times, their livelihood being absolutely cut off, great deprivation and want were endured. The expensive freightage to and from the great markets of Liverpool and Manchester was a constant and heavy handicap against the success of the trade, and contributed no little to its instability.

And the distress inflicted upon the weavers in these periods was often accentuated by ill-advised political enactments. Farish writes:- "The year 1815" (the year of Waterloo), "when the Corn Laws were enacted almost at the point of the bayonet, inaugurated a period of calamity in this country, especially for those in the cotton industry, never surpassed in any nation, and, thank goodness, rarely equalled in our own. That unrighteous, measure, with others equally wicked, so crippled commerce that work and wages become reduced to the lowest point, while the cost of every necessary became correspondingly increased. The cry of discontent and the wail of famishing women and helpless children were heard in every street. How little the legislators cared for the unmerited sufferings of the multitude may be read in the records of the times .... and the trials of men sent to prison for nothing worse than asking for bread for their little ones. It was truly heart-rending to hear the stories my mother used to tell of the hunger and hardship they endured from 1814 until 1820."

HARD TIMES AND SHORT COMMONS

"The winter following the hot summer of 1826 was a terrible one for the working people everywhere, and the hardships fell with unwonted severity upon the North-country weavers. The benevolence of the gentry was taxed to the uttermost to preserve their poorer neighbours from actual starvation. To utilise these gifts in Carlisle, the weavers were employed to construct the walk - the Weavers' Bank leading from the Castle to Eden Bridges - which still remains as memorial to the honour of some, and a reproach to those others who wickedly helped to maintain the iniquitous bread tax in the face of a starving community. Unsound barley meal that year sold for as much as four shillings a stone" - half the week's wage of a common labourer - "while wheat flour and butcher's meat were wholly beyond the reach of the ordinary workman."

"It was no uncommon thing for our house to be without bread for weeks together: and I cannot remember to have ever seen, in my very early years, a joint of meat of any kind on my father's table; oatmeal porridge and potatoes, with an occasional taste of bacon, being our principal food. Once, for six long and weary weeks at a spell, no bread entered the door; that extreme restraint being needed to enable my father to pay a few shillings of rent in arrears..... I well remember the 'love-feast' that ended that period of semi-fast, and the happiness with which my father filled my little hand with the first crust of bread."

GROPING FOR LIGHT - EDUCATION

Touching, indeed, is it to recall the heroic strivings of the half-starved poor for instruction and knowledge. In circumstances where the material needs of life made such early, constant, and exorbitant demands upon their time, their interest in education almost puts to shame the lackadaisical unconcern and everything-made-easy demands of to-day. We might with advantage in these days emphasise a little more the supreme importance of individual effort in our educational programme. Our privileges over those who lived a hundred years ago are many and great; greater yet will they be in the future; but the best of systems depends for its success upon individual effort. There is no royal road to learning - or anything else worth having, "If you want knowledge you must toil for it. Toil is the law," wrote Ruskin. Fuller opportunities and better facilities for education demand more and more complete consecration and concentrated service in the aspirant.

There was little in the circumstances of William Farish to awaken a desire for mental improvement, and scant facilities to support such inclination when awakened; but the desire came, and the good use made of the few and faulty opportunities meant much to him in later days. "My short course of schooling began," he writes, "in my sixth year, with an old crippled Irishman, Billy Morgan, in a room in a lane off John Street... My next school was the Free School near the Sallyport on the West Walls [of the city]; but my schooldays came to an end at the age of eight, when I was put to the bobbin-wheel; and I was raised to the loom before my tenth year was attained."

LEARNING TO READ

In the light of subsequent events it is interesting to note that this boy, who in later life did a considerable amount of journalistic work, edited a newspaper, was a public speaker, and filled with credit a high civic office, was practically self-taught. In learning to read he never had any set lessons, save an occasional one from his father. "I acquired the art of reading while spelling out sentences in the newspapers to the weavers, while they kept on throwing the shuttle;.... thus, with corrections from one and another I learned to read."

At a later date his longing for education was intensified by seeing Harry Lonsdale (Dr. Lonsdale, author of the "Worthies", young Heysham, and other "comfortably clothed, plump and well-fed boys" (there's a world of revelation and pathos in those words), passing through Caldcoats to and from the Rev. J. Wilson's school at Coledale Hall (once again to be associated with a branch of education). Farish was enabled to gratify this longing, to the extent of learning to write a little, and to acquire a smattering of the first rules of arithmetic, under conditions that strike us to-day as peculiar and fantastic. There was a night-school run by "an inmate of the workhouse," named Jemmy Wymms, who, to provide himself with tea and snuff, was permitted to open an evening school in Caldcoats, which the lad attended for one winter session.

POLITICS - A BAPTISM OF FIRE

Times and circumstances compelled that "a lad of parts" like Finish must inevitably gravitate to politics. Through the aching breast of labour "ran a thrill of joy prophetic," presaging a new era; and politics was the avenue leading to a 'promised land" of all-round betterment. Great movements were afoot. Chartism inspired high hopes and high endeavours - "The best of life was yet to be."

We have seen that this lad "learned to read by spelling sentences in the newspapers to the weavers." The weavers were ardent politicians, and Farish was thrust into politics through his literary services to these busy men. Carlisle had been for some time in the vortex of political ferment, and had but recently succeeded in freeing itself from the incubus of the civic intrigue of Sir James Lowther. The heat of battle yet ran warm in the blood, and kindled the zeal of the weavers. In the struggle they had acquired a certain independence. As a result, they boldly expressed their well-informed opinions, and sometimes were inclined to demand their rights though means that were, perhaps, pardonable, though infelicitous - at times disastrous, ending, as they did, in serious rupture.

Farish was introduced to active politics at a very early age. He was six years old at the time and attending Morgan's school in John Street. "I was in the school during the firing of the gallant 55th at the election of Sir Philip Musgrave. The Radicals of the neighbourhood had offered some indignity to the Tory candidate, and the then Mayor, Mr. William Hodgson, thought fit to 'let slip the dogs of war' and several people were wounded; one little girl, named Birrell, was shot dead in the dame's school near to ours, and it was lucky we did not get a 'baptism of fire.'"

A PRACTICAL LESSON

This incident of the election is thus described in Creighton's "Carlisle" :- "Many of the freemen were weavers, who suffered from variations of trade, and freely expressed their discontent. In 1826 Sir Philip Musgrave, the Tory candidate, was beset by a body of weavers during his canvass, was forced to flee into a house where the owner gave him shelter, only on condition 'that he should sit down and work at the loom, to improve his practical experience of the life led by many of his constituents.' The Mayor went to quell the riot, accompanied by all the civic force of the town, namely, two constables. The mob seized the Mayor and ducked the constables, whereupon the soldiers of the garrison were called to their assistance, and there was some bloodshed. Next day the arrival of the Liberal candidate, Sir James Graham, of Netherby, led to renewed rioting. As a precautionary measure a body of cavalry had been stationed near the town by order of the Mayor. This caused great indignation among the people, and the Mayor, losing his head, denied that they were there. When their presence was discovered the mob rushed upon the Mayor, who was only saved by Sir James Graham. Terror brought on a fit of apoplexy, which for some days threatened the Mayor's life. Finally, the tumult was appeased by Sir James Graham, who arranged that the cavalry should withdraw to a distance of four miles from the city."

"The whole matter is a sample of civic incapacity. It was ridiculous that Carlisle, with a population of 16000, should only have two constables; but the Corporation had steadily refused to increase the number, on the ground that the presence of a garrison within the city was a sufficient guarantee for the maintenance of order. They disregarded the fact that military interference is more likely to create than to allay a disturbance amongst Englishmen."

THE REFORM BILL

The years from 1828 to 1832 were momentous years in European history. Poland, The Netherlands, and France were all in their several ways making strenuous efforts for freedom. Britain was in travail with Catholic emancipation and the first Reform Bill. In Carlisle the interest was intense; the desire for the latest news keen to anxiety, and not to be satisfied by the services of the local press alone. There were no railways to distribute news everywhere in a few hours; no telegraphs to waft the latest political speeches to distant provinces almost before the echoes of the spoken words ceased to vibrate; so the weavers used to club their pennies together to obtain the London newspapers, and in great excitement await the arrival of the mail coaches that brought them. The "Weekly Dispatch," with its accounts of the rick-burnings and reform meetings and the tri-weekly "Evening Mail," issued by "The Times," giving a resume of the previous two days' news, were the favourites. At the height of the reform agitation the weavers gathered round the fire in Farish's shop about nine o'clock in the evening, and with the boy in the middle of them as reader - they themselves being unable to read - would go through the debates until long after midnight.

The passing of the bill was an occasion of general rejoicing; "and," writes Farish, "few places excelled the Border City in giving effect to the public gratification. I have seen many political demonstrations in Carlisle, but none to surpass that one in enthusiasm and public spirit. The gentlemen of the town subscribed liberally to the necessary funds, and the trades vied with each other in giving eclât to the proceedings. The streets were made gay with flags, political mottoes, and evergreens; and the procession was imposing and of immense length. In the vanguard was the manly form of John Dixon, and with him were James Steel (of the "Journal "), Peter Dixon, James Ross, Robert Bendle, and others, who, having led the campaign, were well entitled to the honours of the victory. It was arranged that all who walked in the procession should have dinner, part being paid by the person himself, the remainder from the general fund,"

THE HAND OF AFFLICTION

The vicissitudes of life are strangely incongruous: the hidden hand of fortune may be suddenly extended from beneath the folds of the mantle of time in benediction or in chastisement - we know not until we are blessed or smitten. The public jubilation over the Reform Bill was succeeded by a period of tribulation, the like of which, happily, the advancing science of hygiene largely prevents today, for shortly after the festivities the cholera swept like an angel of death over the country, claiming a heavy toll among the ill-nurtured poor in the city.

"Few families wholly escaped. In some instances the breadwinners were taken and helpless orphans left! In others the children were swept away and the parents only spared. The authorities of Carlisle posted up at the Market Cross the daily return of cases and deaths. I frequently went there, protected by a small bag of camphor depending from my mouth, to bring home the sombre record." The virulence of the plague gradually waned with the approach of cold weather, but left behind, in town and hamlet alike, the sear-mark of its visitation.

LACK OF HEALTHY RECREATION

Popular pastimes help us to understand the general life and conditions of the people. Those happy circumstances where the worker "minds his labour wi' an eydent hand," where he has steady employment under decent conditions, and receives fair remunerative recognition, favour an intelligent use of his leisure. Where, however, employment is irregular, or carried on under oppressive conditions, where long hours of drudgery are exacted, and wages are insufficient to provide decent food and clothing, his scant spare time is not unnaturally frittered away in pastimes which promote irregular habits that further vitiate and debase. In view, therefore, of the arduous and precarious conditions under which the workers - weavers and general - toiled for their daily bread, it is not surprising to find that Farish gives a depressing picture of "sport" in the "thirties." Generally speaking, popular relaxations were found in politics and in public-houses, the former conferring a stability and edification which the latter, too frequently, dissipated and destroyed.

"Long before 1835," he writes, "the infamous Beer Bill was in full swing everywhere, and in few places more vigorously than in Carlisle. The people being ardently political, honoured many of their champions by making their portraits do duty as ornaments above the doors of these resorts. Lord Brougham, Earl Grey, Harry Hunt, and Andrew Marvel were very prominent: but the greatest daub was a presentment in the Willow Holme of "Billy James," the Radical of Barrock Lodge. Inside these houses the fame of the politician was divided with that of the heroes at the prize ring. The names of Jim Ward, Deaf Burke, Sandy MacKay, and Dutch Sam were much better known than either the Prime Minister or the Prebendaries of the Cathedral. The owners of these beer depots could keep their taps running in those days every hour that God sent, except perhaps a brief space now and then in church hours, when Bumbledom [meaning church officials] happened to sally out. In some parts of the town riot, rowdyism and blasphemy reigned supreme, and in the early hours of Sunday morning they were literally like pandemoniums."

"One enterprising genius had a den fitted up behind Ritson's Lane, an infamous place, half-house, half pavilion, where he carried on a roaring trade. I witnessed a fight there myself one Sunday morning between two local pugilists, Peter Gardner and Billy Smith, which lasted from one to three o'clock, without the slightest interference by anybody in authority. Bacchanalian songs and amorous ditties, with the doggerel of the street ballad-mongers, were always popular, while a libidinous toast or sentiment was sure to bring down the house. These were the sort of surroundings into which I had drifted by my seventeenth year."

THE SUBMERGED TENTH

The irregularity of employment and frequent depressions periodically increased vagrancy, the ranks of the regular Nomads being swelled by the victims of bad trade. At such times many respectable workers endeavoured to eke out an existence by peddling small wares among a community scarcely better placed than themselves. Others "took the roads," tramping in search of employment, or merely at the urge of restlessness - "most pleased when most uneasy " - and thus the "Padding Can" or common lodging house, in which these destitute wanderers sought shelter and herded with the flotsam of society, came within the experience of many weavers broken on the wheel of adversity.

The lowest of the common lodging-houses were hot-beds of demoralisation and infection, where any ragamuffin who could muster threepence to pay for a corner was admitted. One such house had only two rooms, one on the ground serving as cooking kitchen, dining-room, smoke-room, and general room: the, other, overhead, having four beds in its limited space, serving as a common dormitory. The evening meal as supplied to the wayfarer varied according to his or her means and time of arrival: the mendicant of limited purse - or rag, for money was usually carried rolled in rags - who, arriving late, depended on the larder of the proprietor, might be regaled with a feast of a "pennorth" [penny worth] of "salt-mat," (red herring, or coarse fish), a "pennorth" of bread and a "pennorth" of boiled tea, or "het up kail," [heated up broth made from greens] served in a dish or mug. The unfortunate who only mustered threepence for his "doss," fed fat upon the mixed smells and anticipations awakened by the pungent aroma from the frying onions of a comrade more opulent.

FARISH'S DEGRADATION AND C0NVERSION

William Farish had his taste of vagabondage while in his later teens. He sowed his wild oats of dissipation and reaped his harvest of destitution before he was twenty-two years old. He was then lodging at Kingstown; and, he writes, "I was literally without a second shirt to my back, no coat, and only a pair of pants that I had bought for nine-pence at a second-hand shop in Annetwell Street; my feet being encased in clogs made out of old boots at a cost of one and threepence [a shilling and three pence], paid to a clogger at Stanwix." A feeling of revulsion set in, and he made a determined and successful effort to break away from those habits which were directly responsible for his humiliation. Making a clean cut against intoxicants, he signed the pledge (continuing throughout a long life a staunch teetotaller), settled down to work, betook himself again to books and reading, and interested himself in popular educational ventures like the Adult School and the Working Men's Reading Room Movements.

"Curiously enough, the first two books that came my way were the 'Autobiography of Franklin' and Harvey's 'Meditations,' ..... they exactly suited my condition, and were a timely stimulus. Along with my reading I set about improving myself in accounts and penmanship. With Walkinghame's arithmetic I used to con over the problems as I worked the treadles. During the winter I assisted Mr. MacVennells in his school in Stanwix during the day, in return for my dinner and his help in my studies; the nights and early morning being given to the loom to earn the cost of my lodgings and other food. By the Easter of 1841, when I returned home to my father's, I had got some decent clothing, and also a fair mastery of Walkinghame."

FARISH AS SCHOOLMASTER: BLACKHALL SCHOOL

By 1842 Farish had made sufficient progress in learning to open an evening school. "I soon had a good supply of pupils, and that was my first little step forward. Hearing soon after this that the township school at Blackhall was vacant, by the good offices of John Rayson, the former master " - one of the Cumberland Bards - " I got permission to re-open it. Thus I was able to bid adieu to the loom. For over two years I walked daily between Newtown and Blackhall (he was then living at Newtown) [a distance of about 2˝ miles each way], and my remuneration never exceeded 9s. a week. With that, however, and a sort of permissive 'whittlegate'1 among my pupils, I did very well."

Young Farish's circle of friends and acquaintances was now such as any man might be proud of, and his numerous comments on men and affairs in the city are interesting reading. In 1844 he suffered a reverse of fortune that changed the current of his life. In that year the school at Upperby was re-opened, and some of his scholars from that village transferred from Blackhall School to it. The loss of pupils reduced his earnings to below subsistence level. Just then, however, Messrs. Dixon, of West Tower Street, offered him a situation as a warper. Warping was looked upon as a respectable and lucrative employment. "So, although all my leanings were towards intellectual pursuits, and I felt it hard, after so much toil and preparations, to turn again to manual labour, I thought it best to close my school and enter this new occupation."

A BEWCASTLE WIFE

With regular employment came a desire for a wife and home of his own, and in 1845 he was on the "look-out." "Although in constant employment I felt the difficulty of inviting any respectable woman to share the luxuries of at most 16s. a week. But, luckily, that 'Divinity which shapes our ends' found her, who has ever since been my partner, and the sharer in all my ups and downs, joys and sorrows. She was the eldest daughter of Thomas Clemitson, who for over half a century occupied the large farm of Kilnstown in Bewcastle. 'My Bessie' as I called her, first at Brampton and then at Carlisle, learned the millinery and straw hat business, and was so employed in the city when I made her acquaintance.

BEWCASTLE HOSPITALITY: A TYPICAL STORY

"The natives of Bewcastle are almost proverbial for their uprightness, thrift, and industry. Their hospitality to strangers is generous beyond measure." (An assertion which the "Carel Lads" can support, as they have a vivid and grateful memory of Bewcastle hospitality received at the hands of Miss and Mr. Dobson, of Holme Head, when they visited the famous Christenbury Crags) [now Christianbury Crag, near Bewcastle]. "Being at Stapleton Rectory at Christmas, 1844," continues Farish, "I was taken on a ramble to the Gillillies2 [now Gillalees] and the Ringing (Rinion) Hills [now Rinnion Hills], where the kindness that was shown to us was something approaching to princely. Goose flesh and liquor were exceedingly abundant and supplemented with all the other rarities welcome at that festive season. Returning we called in at Askerton Castle and found the worthy laird - 'Auld Tom Tweddle' - nursing at the same time a big gouty foot in a band box, and a huge whisky jar at his elbow. Our first salutation upon being announced was a hearty one, that 'the Bwoys sud step forrit and nit be bleate, but help theirsels to the speerit,' and when told that one of us did not so indulge, 'The Lword 'a mercy on us,' exclaimed the jolly yeoman, 'what sort o' a chiel mun he be 'at refuses a drop whusky at an ora teyme.' "3

At Christmas, 1846, Miss Clemitson became Mrs. Farish, the wedding taking place in St. Cuthbert's Church, Carlisle. Their first home was in Glover's Row.

A POSITION OF TRUST

Three months after marriage, a friend of his wife offered Farish a situation as timekeeper on some railway work in Cheshire at the salary of 26s. a week. Farish accepted, and left his native city. With his removal from Carlisle ends his connection with 'Memories of Old Carlisle'; though he always continued to take an interest in the old city, and on several occasions contributed to the columns of the "Journal."

William Farish was an interesting personality, and his career - considering the disadvantages of early circumstances was remarkable. After many ups and downs, he settled in Chester, and was for some time editor of a newspaper. He was a militant temperance advocate; an ardent politician and reformer; a respected and enthusiastic public worker; while in November, 1877, he was elected to the supreme office of Mayor of Chester.

In his 70th year he wrote; "Any small success in life, which I may have achieved has not been the result of either brilliant talents or special genius, but rather of the simple, ordinary practice of industry, thrift and economy." The lesson of his life seems to be that "persevering mediocrity is much more respectable, and unspeakably more useful, than talented inconstancy."

OTHER CARLISLE FIRMS WITH A HISTORY

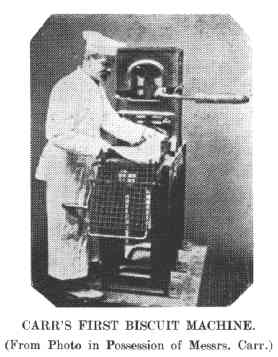

"The stranger who visits Carlisle," said a writer of 1859,

"should not forget that the manufacture of fancy biscuits by machinery has long been

successfully carried on in the establishment of Carr and Co., of this city.... The

peculiar character of the manufacture, as well as the modus operandi, often excite

the wonder and admiration of the numerous visitors to these interesting works."

"The stranger who visits Carlisle," said a writer of 1859,

"should not forget that the manufacture of fancy biscuits by machinery has long been

successfully carried on in the establishment of Carr and Co., of this city.... The

peculiar character of the manufacture, as well as the modus operandi, often excite

the wonder and admiration of the numerous visitors to these interesting works."

THE FIRM AND ITS WORKERS

But twelve years before this date, according to an 1847 directory, the establishment was regarded as the most complete of its kind in the country, "the whole process, from grinding the corn to finishing the biscuits being performed on the premises.... The machine, which cuts the biscuits into various devices, makes from 90 to 109 per stroke, or about 300 per minute. The quantity of fancy and other biscuits made annually is from 400 to 500 tons, and they find their way to nearly all parts of the globe."

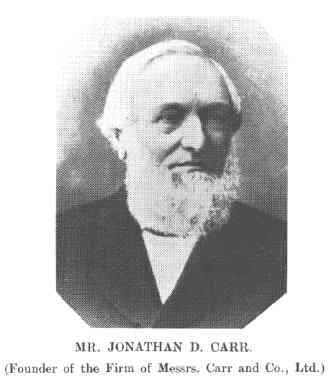

To-day a single machine will turn out from 3 to 3˝ tons per day, though, of course, the quantity varies considerably with the quality and size of the biscuit. The success of the firm has been largely due to the considerate treatment of its employees. Contented workers may generally be counted upon to produce the maximum quantity and the very best quality of work; and in providing rest rooms and other conveniences for their "hands," the present directors, with Mr. W. Theodore Carr, M.P. for the city, at their head, are but emulating the example of that worthy founder of the firm, the late Mr Jonathan Dodgson Carr, for in 1841, the report continues, "a schoolroom, library, and reading room are attached to the premises for the daily use of young and old in the establishment. There is also a bath, fourteen feet square, supplied by waste water from the steam engine, at a temperature of ninety degrees, for the health and comfort of the workmen."

THE FOUNDER OF THE FIRM

Mr. Jonathan Dodgson Carr, the founder of the firm, commenced business in Carlisle in 1831, and visitors to the works will note the beam which was once over his shop front and bore his name. In those days machinery for the manufacture of biscuits was unknown, every process being carried out by hand; and it was to the initiative and perseverance of Mr. J. D. Carr that England - now one of the greatest biscuit manufacturing countries in the world - owed its first biscuit machine, its first dough-mixing machine, and many other improvements in the manufacture of those delectable morsels which still issue from these works to find their way to every corner of the civilised, and even the semi-civilised world, for branches have been opened in such out-of-the-way places as Khartoum, almost in the heart of the "Dark Continent of Africa.

THINGS NEW AND OLD

The present representatives of the Carr family are rightly proud

of the humble beginnings of the famous firm, with which for nearly a century their name

has been honourably associated. The old hand-ovens are still there, heated by coke, being

still found indispensable in the manufacture of certain biscuits; and the attention of

every visitor is directed to the first hand machine used there for stamping and cutting -

a machine which led to such success that the founder was honoured by being appointed

"Biscuit Baker to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, by Special Warrant, dated May 8th,

1841," up to which date he was the sole maker of machine-made fancy biscuits in Great

Britain.

The present representatives of the Carr family are rightly proud

of the humble beginnings of the famous firm, with which for nearly a century their name

has been honourably associated. The old hand-ovens are still there, heated by coke, being

still found indispensable in the manufacture of certain biscuits; and the attention of

every visitor is directed to the first hand machine used there for stamping and cutting -

a machine which led to such success that the founder was honoured by being appointed

"Biscuit Baker to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, by Special Warrant, dated May 8th,

1841," up to which date he was the sole maker of machine-made fancy biscuits in Great

Britain.

Little did the founder dream of the subsequent results of his efforts - immense buildings covering several acres of ground; doughing rooms, where huge mixing machines are capable of dealing at one time with a quarter of a ton of flour and various other "tasty" ingredients that go to make up a biscuit; "travelling" ovens like heated tunnels, into which pass pans or trays, laden with thousands of pieces of shaped dough, to emerge from the far end a few minutes later ready for packing in tins produced in another part of the premises; icing and decorating rooms where smart-looking girls in their neat overalls are busily engaged in decorating or icing biscuits; a magnificent building given over to the production of toffee and chocolate; and packing and forwarding departments, where nimble fingers are filling tins, and busy hands are packing them, before they are drawn by the firm's locomotive, the "Dispatch," to the North British Railway lines, to find their way to the home markets and more distant places abroad. Truly, a firm of which Carlisle has good reason to be proud.

CARLISLE'S DECORATED TIN BOXES

Almost as well known as Carr's biscuits are the decorated tin boxes produced in their extensive works in James Street by Messrs. Hudson Scott and Sons. In these works, as at Holme Head and in Caldewgate, there is evidence of that twentieth century desire to secure excellent work by ameliorating the daily lot of the worker. All mechanical work must be more or less unattractive, even irksome; but where, as in several of the Carlisle works, working hours are reasonable, and masters allow a practical interest in the physical and mental welfare of their workers, that unattractiveness is reduced to a minimum, and the worker is thereby encouraged and helped to keep himself or herself in a fit and proper condition to turn out work which will meet with the approbation of the public, and "bring grist to the mill" - alike to employer and employee.

THE FIRM'S HUMBLE BEGINNING

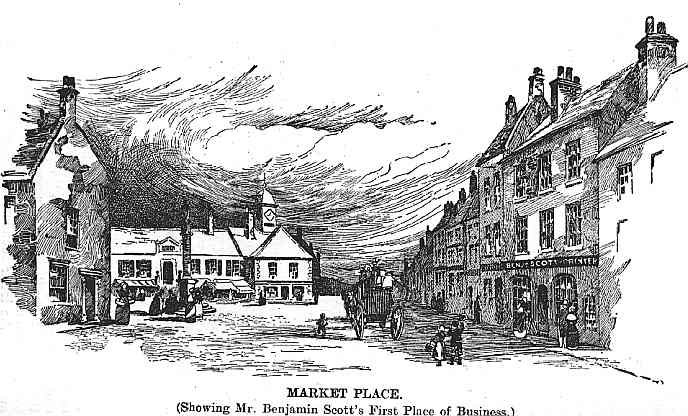

Just at the end of the eighteenth century - in 1799 - the people of Carlisle learned from an announcement in the "Cumberland Paquet" that a Benjamin Scott was commencing business as a "printer, bookseller, stationer, and patent medicine vendor" in "a commodious house in the Market Place." The announcement, however, was somewhat premature, Mr. Scott's plans "going agley," owing to the letter founder not being able to complete his assortment of types in the time he promised." The shop, however, was opened on June 15th, and the business was well established in 1805, when the name of the founder appeared as the printer of a handbill convening a meeting of the citizens in the Town Hall to promote the relief of widows and orphans rendered destitute by the loss of their husbands and fathers at Trafalgar.

LITHOGRAPHY AND TIN BOXES

Mr. Benjamin Scott was succeeded by his nephew, Mr. Hudson Scott,

who showed his enterprise by being among the earliest printers to put down a cylinder

printing machine driven by steam. Lithography - the process of printing from the flat

stone discovered by Senefelder in 1796 - was added some time during the forties, and

from that time the business rapidly extended, so much so that soon after it was taken over

by Mr. Hudson Scott's sons, Mr. Benjamin (now Sir Benjamin) and Mr. W. Hudson Scott, in

1868, it was found necessary to look round for a still more "commodious house,"

choice being then made of the present site of the works in James Street.

Mr. Benjamin Scott was succeeded by his nephew, Mr. Hudson Scott,

who showed his enterprise by being among the earliest printers to put down a cylinder

printing machine driven by steam. Lithography - the process of printing from the flat

stone discovered by Senefelder in 1796 - was added some time during the forties, and

from that time the business rapidly extended, so much so that soon after it was taken over

by Mr. Hudson Scott's sons, Mr. Benjamin (now Sir Benjamin) and Mr. W. Hudson Scott, in

1868, it was found necessary to look round for a still more "commodious house,"

choice being then made of the present site of the works in James Street.

Subsequently tin-box making was added to the business, and vast improvements and extensions followed, "Slater's factory," on the opposite side of the street, being taken over to accommodate the ever-growing army of clerks, artists, lithographic printers, tin-box makers, and others who today find employment here in the production of artistic posters and show cards and decorated tins of every description.

"Every advertiser recognises," wrote a representative of the "Journal" in 1913, "the advantages of the artistic poster or show card, and everybody who has had to purchase goods generally sold in packages knows the seductiveness of the neat tin box or case bearing an artistic design, whether it be in the form of soap or tobacco tin, a capped talcum powder bottle, a chocolate box to be used afterwards for handkerchiefs or gloves, or an elaborate tin canister, biscuit box or vase, which remain as useful and artistic ornaments in the house when their original contents are exhausted. Of the uses to which the tin box has been applied, it may be said that there is no end, and to meet a demand which is ever growing for decorated boxes of every description, for attractive advertisement sheets, cards and labels, the works of Messrs. Hudson Scott and Sons, Ltd., have been developed until they hold the first place of the kind in the country."

ANOTHER OLD-ESTABLISHED PRINTING WORKS

The reference to Mr. Benjamin Scott as a "patent medicine vendor" takes us back to times in Carlisle when, as in country places to-day, shops were few and far between, and multiple shops had perforce to supply their customers with foods, medicines, articles of apparel, and almost any form of commodity of which they had need. Very recently an employee of Messrs. Charles Thurnam and Sons - a firm occupying premises where books and stationery and similar articles have been sold since the eighteenth century - discovered labels upon some old drawers which had evidently contained "Cockle's Pills," and other cure-all remedies for ills to which our ancestors, like ourselves, were liable.

Mr. Scott's original premises are generally known to-day as the "Patriot Office," though the "Patriot" is now non est. This paper was first printed by Messrs. Thurnam, behind whose shop once lived and worked Mr. Jollie, for some time Carlisle's leading printer and stationer, and the founder of the "Carlisle Journal."

Messrs. Thurnam, by the way, have recently added to their premises the "Old Jail" in King's Arms Lane, where workmen engaged last year in making excavations unearthed from the clayey floor a human bone with an effluvium which, needless to say, brought the work to an end. How strange it is that so little is known of this mysterious fourteenth century building.

DILIGENT IN BUSINESS

An interesting photo in oils of the founder of this old printing establishment, Mr. Charles Thurnam, with another of Mrs. Thurnam, is still on view in the shop. Strictly punctual and diligent in business himself, he expected his workers to follow his example, and tradition asserts that he kept on the premises a whip for the chastisement of late and unruly apprentices and others who failed to live up to his requirements. "Other times, other manners." Such zeal to-day would probably result in a police court fine, and a decrease rather than an increase of business.

When the present representatives of this firm celebrated its centenary in 1916, the total service of four of its employees approximated to a couple of centuries - Mr. Rowley Smart, printers' overseer, 44 Years; Mr. R. Sowerby, printer, 49 years; Mrs. Mary Innes, bookbinders' forewoman, 49 vears; and Mr. George Batey, printers' foreman, 44 years - all four of whom, it is interesting to note, are still "going strong."

PRINTING IN ITS INFANCY

In early days, says Mr. Smart, "all composing was done by hand. Then there were no delicate and intricate type-composing machines to do 'rush work,' of which there was often plenty; with the result that working hours often ranged from 6-30 a.m. till midnight, even Sunday labour being necessary to meet the insistent demand for 'literature' which came with a general election. At such times it was 'slog, slog, slog' for weeks together, and one wonders what would then have been the life of a printer if the multifarious Government forms of to-day had been in existence."

"Printing machines, too, were then in their infancy and generally conspicuous by their absence. All bill work and 'short runs' were done on the old-fashioned lever press, and for a pressman to put in a day's work at one was horse-work. Over one job I remember - 900 three-sheet double-demy posters, each sheet printed in three colours, for the benefit of a circus - the pressmen showered curses loud and deep. It was winter time, and a hard frost, and the ink could not be properly distributed without burning below the ink table a number of gas jets, which made the roller soft and 'tacky,' causing the poor 'devil's' hands to blister and bleed. No wonder 'words,' both old and new, were poured upon all circuses and shows before that job was ultimately finished."

"With the advent of the cylinder printing machine wonderful strides were made in the advancement of the typographic art. The 'Belle Sauvage' in its day was a wonder, but step by step improvements were effected, till, as a 'jobbing machine,' the Miehle arrived to prove itself facile princeps."

CARLISLE'S GIANT CRANES

This reference to machines is a reminder that in Carlisle - at the St. Nicholas works of Messrs. Cowans, Sheldon, and Co., Ltd. - are manufactured some of the most prodigious engineering devices known to the world of mechanics.

In 1847, about a decade after the opening of Carlisle's first railway, when these "iron roads" were just beginning to bring the city into closer touch with the world outside, Messrs. Cowans, Sheldon, and Company's first works were established at Woodbank, on the left bank of the river Petteril about a couple of miles from Carlisle, the partners at that time being Messrs. John Cowans, Edward Pattison Sheldon, and William Bouch. At the beginning the firm was mainly occupied in the production of general railway plant. A later development was the construction of cranes, which ultimately became the Company's chief speciality, and has gained for it world-wide renown.

A TURNTABLE INVENTION

In the early days of railways the method of reversing the position of locomotive engines was by means of turntables slowly worked round by gearing. Turntables on the central pivot system, by which the weight is balanced on a central steel pin working in a steel cup, were first introduced and built by Messrs. Cowans, Sheldon, and Co., and have been largely supplied by them, not only at home, but for India, Egypt, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and South America, as well as for the continent of Europe. This invention enables the heaviest engines to be easily turned round in less than a minute by one man, who walks round the circumference of a turntable pit, pushing a lever attached to one of the turntable beams. The same principle was also adapted to turntables for carriages and waggons, and has long universally superseded the original geared turntables.

WOODBANK TO ST. NICHOLAS

In 1858 larger and more convenient promises were found to be necessary for the firm's extending work, and the engineering department of the works was transferred to St. Nicholas, Carlisle. It was then that the firm was joined by the late Mr. George Dove. Meanwhile the Woodbank Works were continued for the manufacture of forgings, railway wheels, points and crossings, and other articles of use on railways.

About 1860 the original partners of Cowans, Sheldon, and Co. - Messrs, John Cowans, Edward Pattison Sheldon, and William Bouch - founded the first ironworks at Darlington, and in due course the whole of the Woodbank undertaking was transferred there. Although they were founded, and originally exclusively owned, by the three partners named, Cowans, Sheldon, and Company as a firm never had any interests in these Darlington works, which are now known as the "Darlington Forge, Limited," and rank among the largest and most important works for the manufacture of steel forgings and steel castings in the kingdom.

A MONSTER FLOATING CRANE

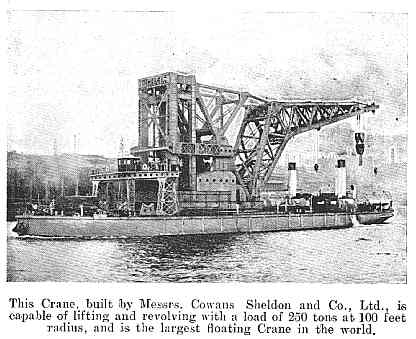

The works at St. Nicholas have also been

enormously increased, and now extend to seven acres, mostly covered with substantial

buildings fitted with up-to-date machinery of the heaviest class. In particular, the

Company has attained pre-eminence in the design and manufacture of floating cranes, having

built the largest of these cranes in the world. One which they now have in course of

construction is designed to work and revolve with a load of 350 tons, its power exceeding

by 33 per cent. that of any floating crane at present in existence.

The works at St. Nicholas have also been

enormously increased, and now extend to seven acres, mostly covered with substantial

buildings fitted with up-to-date machinery of the heaviest class. In particular, the

Company has attained pre-eminence in the design and manufacture of floating cranes, having

built the largest of these cranes in the world. One which they now have in course of

construction is designed to work and revolve with a load of 350 tons, its power exceeding

by 33 per cent. that of any floating crane at present in existence.

But although the firm's speciality, as has been said, is lifting appliances, they also execute engineering work of every kind.

The present directors of the Company are Major Thomas Bouch (chairman), Mr. John Charles Dove, Mr. James Walter Brown, Mr. Harold Edward Carter, and Mr. John Barrington Pearson, who is managing director.

Carlisle, as the school geography book has it, "is now a great railway centre, and has long been noted for its silesias, its biscuits, its decorated tin boxes, and its giant cranes."

Two Carel Lads (George Topping and John J. Potter), Memories Of Old Carlisle, 1922.