Just before starting there is the usual bustle so dear to the hearts of coachmen and grooms; then the horn is sounded, all passengers are seated, the driver tightens the reins, and we are rattling over the stony street. A turn to the left, and again to the right, and the long climb of Castle Rigg is begun; at the top, a thousand feet above Keswick, the coachman draws in his steeds for a few moments, and, looking back, a glorious prospect spreads before us. The town, lit up by the morning sunlight, lay like a dream far below us; the hills to the west are in deep shadow; the mountains north of Borrowdale are ablaze in golden light; Derwentwater gleams like a mirror, and over Crosthwaite Church the long blue bed of Bassenthwaite stretches away.

The morning mist has not yet been dispersed from old Skiddaw and Saddleback. Now we drop down into the vale of St. John. "What a beautiful name," said a lady, "and how suggestive of loveliness"; but not a whit more lovely than it appears, with its streams and grey roofs of white-washed cottages resting under rocks and sheltered by fir woods, with the deep green of meadow land around. Yonder is the Church of St. John. Now we have reached Thirlmere, and Castle Rock, stern and grey, rises above to guard the gloomy pass below. In front is Helvellyn, rising like a mystic curtain wall, as if to bar the entrance to some unknown land. Now the road descends rapidly, the horses dash forth in fine style, the leaders are in a canter. Soon the shrill sound of the guard's horn is heard, and the driver reins in his panting steeds for a short breathing time at the King's Head inn, Thirlspot, a low Antique house, with the fell rising behind.

At Dalehead a torrent, in a series of falls, leaps to the vale below. This is a place of memories; we are in the footsteps of Southey, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Wilson, Foster, Matthew Arnold, and Rossetti. Away over the lake is haunted Armboth Hall; by the shore of Thirlmere is the "Rock of Names," the meeting place of the poets of Grasmere and Keswick, and here they have left a memorial by carving their initials in the rock.

An upright Mural block of stone,

Moist with pure water trickling down;

Thy power, dear Rock, around thee cast

Thy monumental, shall last

For me and mine ! O thought of pain

That would impair it as profane,

And fail not thou, loved Rock, to keep

Thy charge when we are laid asleep."

Near to these rocks was the Cherry Tree

public-house, where Wordsworth stopped his peasant waggoner during his famous drive from

Rydal, over Dunmail Raise, to Keswick.

The sound of the

driver's horn is heard, a light flourish of the whip, and we are off at a swinging pace,

by Thirlmere, silent and peaceful, gleaming below, and far away west, summit behind

summit, and range after range, with wreaths of mist still curling round, as the soft

fingers of distance smooth the stronger outlines and melt the hues of lavish richness into

the setting of the bounding heavens ! onward rumbles the coach, and the blood courses

through the veins quicker as we inhale the pure mountain air. Now we have reached the

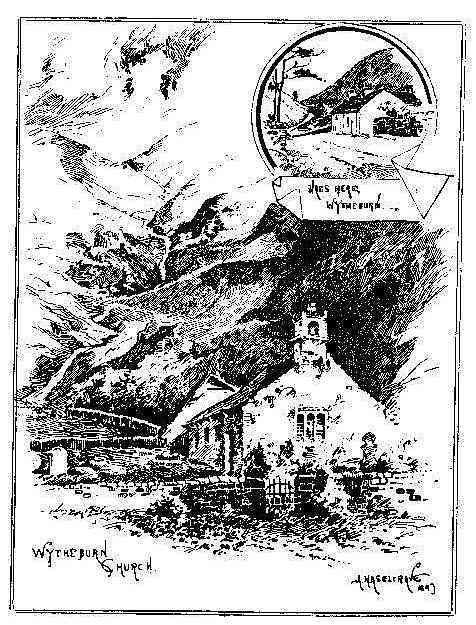

Nag's Head, Wytheburn. Wytheburn's house [church] appears as lowly as the lowliest

dwelling. Coleridge wrote :-

The sound of the

driver's horn is heard, a light flourish of the whip, and we are off at a swinging pace,

by Thirlmere, silent and peaceful, gleaming below, and far away west, summit behind

summit, and range after range, with wreaths of mist still curling round, as the soft

fingers of distance smooth the stronger outlines and melt the hues of lavish richness into

the setting of the bounding heavens ! onward rumbles the coach, and the blood courses

through the veins quicker as we inhale the pure mountain air. Now we have reached the

Nag's Head, Wytheburn. Wytheburn's house [church] appears as lowly as the lowliest

dwelling. Coleridge wrote :-

"Humble it is, and very meek, and

very low.

And speaks its purpose by a single bell;

But God himself, and he alone can know

If spirey temples please him half so well."

In olden time the living was only worth £3 a year, but the parishioners lent the parson a helping hand, besides he had "a goose run" on the slopes of Helvellyn. It was formerly known as the smallest church in England, but of late years it has been slightly enlarged. Opposite to the church is the Nag's Head Inn, which we have found most comfortable on more than one occasion after a stiff day's tramp. It lies at the base of Helvellyn, and from this place is one of the shortest paths to the summit. Still the coach rattles through the hills that peer above clothed with the tints of moss and lichen, past pine wood and winding brook, and now the vale opens to view like a veritable land of enchantment. Helm Crag, with open jaws, in its wraith of ghostly mist, appears as if about to fall on some unwary foe. Here is Dunmail Raise, where the last king of Cumbria was slain, and a heap of stones raised over his corpse, hence the name Raise.* Opposite the base of Helm Crag the driver drew in his steeds for a moment's rest. The foxhounds were searching for Reynard amidst the fastness of the mountain. The black and white of the hounds contrast finely with the dark grey, slatey rock - the music of the baying hounds swells louder as they climb the Helm. They have sniffed Master Reynard, and are bounding over the sharp rock, and the breeze wafts across the vale that loud, eager music of the chase.

Now other objects claim our attention - away to the left is Easalale Tarn

"Tranquil and shut out

From all the strife that shakes a jarring world,"

partitioned off by a screen of rock from the vale of Grasmere, pierced only by a tiny brook threading in silvery line to the lake. This is Easdale Beck, and here is Emma's Dell, which Wordsworth called his own. Here he told the shepherds: "When years after we are gone and in our graves, when they have cause to speak of this wild place, may they call it the name of Emma's Dell."

Helm Crag, with its ever-changing form from lion couchant to cowled priest, or ancient woman, is left behind, the smoke rising from the grey roofs of Grasmere in front. The dewdrops glisten on the leaves of the coppice, the green and brown of the wood, and golden gorse and bracken which clothe the hillsides, sweet surprises and magic charms on every hand. Scene follows scene in one unfailing source of delight. At a steady trot we pass the "Swan" associated with the wagoner, and from whence Wordsworth, Southey, and Scott started to ascend Helvellyn together. Onward speeds the coach, past stream, homestead, and crag. What memories linger around, memories of men now sleeping peacefully beneath the shade of yew trees, in the quiet churchyard, to the music of Rothay's stream ! What romance, pleasure, and fascination ! Yonder is Allen Bank, where De Quincey and Christopher North first met. Both were brilliant among the literati of "Modern Athens." Wilson filled the chair of Moral Philosophy in the University - "a man of fine physique, leonine aspect of head and contour; a mind so equally balanced he could ascend to the highest strain of moral excellence, or descend in his portrayal to the nether extreme" - De Quincey. There are two incidents in his chequered life that are not widely known. A German student enquired of his professor what English author to read, and was told De Quincey. The student's enthusiasm became so great after perusal - came to Edinburgh purposely to see the man who wrote these books, and, strange to say, he found him in a tavern. Sir William Hamilton, the logician, at whose house gathered the Edinburgh men of letters, resolved to have a special night with De Quincey to discuss philosophy. But he at that time, through the excess of opium eating, avoided society and sought isolation. He lived in a rural district (Loan Head) six miles south from Edinburgh. The company sallied forth, found him in a quiet lane, put him into a carriage, wheeled him off to Edinburgh, and when he was primed with the drug he became the lion of the evening. Poor De Quincey! we might truly say of him : "The muse often gives what the gods do not guide."

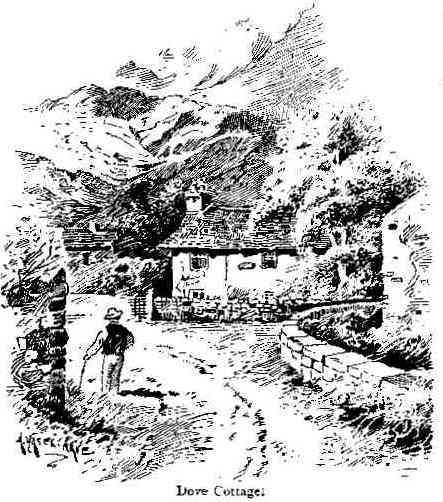

In Dove Cottage, Grasmere, the latter dwelt

for thirty-seven years; here he stored his thousands of volumes, many of which his friends

borrowed, but never returned. It was here he made the acquaintance of the strange Malay

man, and drank so deeply of his dreamful opium. Thus he describes the cottage as he first

it, when on a visit to Wordsworth, who also dwelt here before removing to Rydal Mount:

"A white cottage, with two yew trees breaking the glare of its walls." A little

semi-vestibule between two doors prefaced the entrance into the principal room of the

cottage, which is 8  ft.

high, 16 ft. long, and 12 ft. broad, wainscotted from floor to ceiling with dark polished

oak. There was one perfect and unpretending cottage window, with little diamond panes,

embowered at almost every season of the year with roses, and in summer and autumn with a

profusion of jasmine and other shrubs. Wordsworth, in his "Farewell," wrote -

ft.

high, 16 ft. long, and 12 ft. broad, wainscotted from floor to ceiling with dark polished

oak. There was one perfect and unpretending cottage window, with little diamond panes,

embowered at almost every season of the year with roses, and in summer and autumn with a

profusion of jasmine and other shrubs. Wordsworth, in his "Farewell," wrote -

"Sunshine and shower be with you, bud

and bell,

For two months now in vain we shall be sought;

We leave you here in solitude to dwell

With these, our latest gifts of tender thought.

Thou, like the morning, in thy saffron

coat,

Bright gowan, and marsh marigold, farewell,

Whom from the borders of the Lake we brought,

And placed together near our rocky well."

"Oh, happy garden ! whose seclusion

deep,

Hath been so friendly to industrious hours,

And to soft slumbers, that did gently steep

Our spirits, carrying with them dreams of flowers,

And wild notes warbled among leafy bowers;

Two burning months let summer over leap,

And coming back with her who will be ours,

Into thy bosom we again shall creep."

But here we are at Grasmere - the jewel of Lakeland, the sweetest spot ever man found, rich in associations, the haven of dreams, a spot the most sacred and peaceful. At the quaint lych-gate we part from the coach, for we feel compelled to linger. A holy calm and peace pervades the churchyard, yet the aspect of the ground is slightly changed since the poet wrote -

"Green is the churchyard, beautiful

and green,

Ridge rising gently by the side of ridge;

A heaving surface almost wholly free

From interruption of sepulchral stones,

And mantled o'er with aboriginal turf

And everlasting flowers; these Dalesmen trust

The lingering gleam of their departed lives

To oral record, and the silent heart;

Depositories faithful and more kind

Than fondest epitaph."

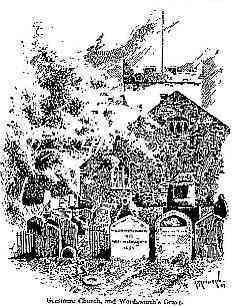

It is not free of memorials now, for the ground is

thickly covered with tombstones.

It is not free of memorials now, for the ground is

thickly covered with tombstones.

Here in St. Oswald's Churchyard, under the shade of yew trees which the poet himself planted, sleep William Wordsworth and his wife; also his sister Dorothy, and near to is the grave of Hartley Coleridge. Few spots make a deeper impression on the soul of the pilgrim than this quiet corner in Grasmere Churchyard. The deep, almost solemn shade of the yew trees, the Rothay gliding past the holy walls and under the grey old arch, its brown waters still murmuring a song as of old, to soothe, as it were, the souls of the immortal bards. The old lych-gate, the surrounding hills - to-day in a blaze of sunlight; the grave mounds at our feet, the antique church with its grey, square, cobbled tower and intricate lines of plaster; the rude antiquities and severe originality of the interior, the unique double arches, with rare oak beam and rafters, and curious Norman font.

"To lie under the mound on which the shadow of that grey tower falls," says one, "seerns scarcely like a banishment from life, only a deeper sleep, in a home quieter, but not less lovely than those which surround the margin of the lake. Voices of children come up from the village street, with the hum of rustic life. From sunny heights the lowing of cattle is heard, and the bleat of the sheep which pasture on the hillsides; and by day and night unceasingly, the Rotha[y], hurrying past the churchyard wall, mingles the babble of its waters with the soft susurrus of the breeze."

Wilson says -

"There is a little churchyard on the

side

Of a low hill that hangs o'er Grasmere Lake;

Most beautiful it is, a vernal spot,

Enclos'd with wooded rocks, where a few graves

Lie shelter'd, sleeping in eternal calm,

Go thither when you will, and that sweet spot

Is bright with sunshine."

The road now passes by the shores of Grasmere. Nothing can excel the charm and beauty of this lake resting in the bosom of the mountains, which are reflected, with trees, meadow, and cattle, as in a mirror. The delicious green of its isle seems like an abode of fairies. The water fowl glide out of the reeds, leaving long streaks of silver on the waters; golden larch and huge fir trees hang their branches over limpid brooks passing to the lake under picturesque bridges; ivy-clad cots, where honeysuckle and woodbine entwine about the rustic porch, and snow-white mullion contrast with the warm green of the meadows - exquisite pictures, a dreamland of the soul.

At the base of White Moss Moor stood the old Wishing Gate. The old moss-grown gate of Wordsworth's youthful days was demolished in his lifetime.

"T'is gone - with old belief and

dream

That round it clung."

"And yet, lost Wishing Gate,

To thee the voice of grateful memory

Shall bid a kind farewell."

It stood on White Moss Common,on the old road from Grasmere to Rydal. Another gate still stands there, but the view is not what it used to be in the poet's lifetime.

Ambleside has two distinct aspects, and

presents startling contrasts - the very old and the new. Ancient lanes, streets, and

archways curve and twist in every conceivable manner and position. The mill-stream and the

old mill, also the bridge house, are tempting subjects to every passing  artist or photographer,

and cottages clinging here and there to the crooked lanes ascending the hillsides form

pleasant pictures. The church is a new, handsome structure, although the spire is not

architecturally all that can be desired. Here, and also at Grasmere, the old custom of

rush-bearing still exists, only instead of rushes to strew the mud floor, the votive

offerings are in the shape of garlands made from rushes and wild flowers. These are hung

on the walls of the church.§ There are several handsome hotels and shops, and a market

square hall and Mechanics' Institute. Some of the streets are very precipitous, and the

manner in which the drivers guide their four-in-hand steeds down, and round the sharp

angles, is admirable. Ambleside is a convenient centre from which to make excursions. It

is aptly named "the axle of the wheel of beauty," every spoke of which holds

gems. Several rivulets join their waters near the town. Up Stock Ghyll are a series of

fine waterfalls, and on the hillside, behind that mass of trees, is The Knoll, for many

years the home of that charming authoress, Harriet Martineau. The sundial on the lawn

still bears the inscription of her heart's desire: "Come, light, visit me!"

Nearly opposite is Fox How, where the good Dr. Arnold dwelt. Further south, above the

shores of Windermere, is Dove's Nest, the residence, for one summer, of Mrs. Hemans.¶

Added to our admiration of the beautiful magnificence and varied scenery of the Lakes, is

that almost holy pleasure which appeals to our higher sympathies and emotion when visiting

the abodes of those children of the muse who have lived here in the past, and who, by the

nobility and goodness of their writings have made these spots sacred, and though now dead

and gone, the music of their inspiration still breathes through the changing years.

artist or photographer,

and cottages clinging here and there to the crooked lanes ascending the hillsides form

pleasant pictures. The church is a new, handsome structure, although the spire is not

architecturally all that can be desired. Here, and also at Grasmere, the old custom of

rush-bearing still exists, only instead of rushes to strew the mud floor, the votive

offerings are in the shape of garlands made from rushes and wild flowers. These are hung

on the walls of the church.§ There are several handsome hotels and shops, and a market

square hall and Mechanics' Institute. Some of the streets are very precipitous, and the

manner in which the drivers guide their four-in-hand steeds down, and round the sharp

angles, is admirable. Ambleside is a convenient centre from which to make excursions. It

is aptly named "the axle of the wheel of beauty," every spoke of which holds

gems. Several rivulets join their waters near the town. Up Stock Ghyll are a series of

fine waterfalls, and on the hillside, behind that mass of trees, is The Knoll, for many

years the home of that charming authoress, Harriet Martineau. The sundial on the lawn

still bears the inscription of her heart's desire: "Come, light, visit me!"

Nearly opposite is Fox How, where the good Dr. Arnold dwelt. Further south, above the

shores of Windermere, is Dove's Nest, the residence, for one summer, of Mrs. Hemans.¶

Added to our admiration of the beautiful magnificence and varied scenery of the Lakes, is

that almost holy pleasure which appeals to our higher sympathies and emotion when visiting

the abodes of those children of the muse who have lived here in the past, and who, by the

nobility and goodness of their writings have made these spots sacred, and though now dead

and gone, the music of their inspiration still breathes through the changing years.

It was the witching hour of sunset as we turned from the road between Ambleside and Grasmere, said to be the finest four miles of coach road in England, and crossed to the west side of the Rothay by one of those charming bridges, half-hidden by leaves, moss, wild flowers, and grass. Under the wooded slopes of Loughrigg Fell we wander, the paths alluring us on through scenes of exquisite beauty and softness. Now we enter the deep shade of the old wood, where overhanging projections of crags cast a sombre hue. Below, through the branches of shady groves, we obtain bewitching views of distant mountains, and can see and hear the Rothay hurrying along, giving forth a dreamful song. From under the trees we emerge into the open glade, past bossy knolls and "heath-clad rocks," where the light from a cottage window, gleamed through creeping woodbine and branch, which half-smothered the walls.

"'Turn where we may,' said I, we

cannot err

In this delicious region - clustered slopes,

Wild tracts of forest ground and scattered groves,

And mountains bare, or clothed with ancient woods surround us."

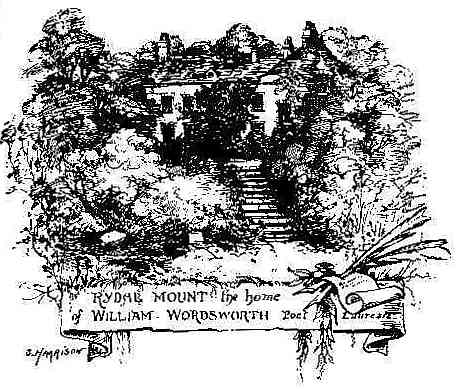

Such were the lovely scenes and impressions

on our mind, of holy calm and pastoral sweetness, as we stood in the twilight before Rydal

Mount, the home of William Wordsworth for 37 years. The spot, ever sacred, is embowered in

branches, and the walls embraced with clinging ivy;  beautiful trees, in all the luxuriance

of vegetation and growth, thrive; ferns, plants, and flowers, both cultivated and wild,

abound, scenting the air with a delicious aroma. Below is the lovely lake, with its tiny

islands, around which immense-limbed trees fling out their arms over green, velvet margins

and grassy, moss lawns, the most lovely. As one has said, nature is a vast Temple, down

whose glorious aisles floats the breath of the Divine! The modest church, peeping from the

branches, and over and above all loom the circling crests of the everlasting hills. Here

lies all that harmony and repose in nature, and that delightful grouping of wood, meadow,

river, lake, and mountain impregnated with the glamour of poetry and the charm of literary

association. Ruminating beneath the branches of an aged tree, we marvelled on the beauty

of the spot; sweetly on the ear came that bubble and even flow of water, and the distant

melody of cascades.

beautiful trees, in all the luxuriance

of vegetation and growth, thrive; ferns, plants, and flowers, both cultivated and wild,

abound, scenting the air with a delicious aroma. Below is the lovely lake, with its tiny

islands, around which immense-limbed trees fling out their arms over green, velvet margins

and grassy, moss lawns, the most lovely. As one has said, nature is a vast Temple, down

whose glorious aisles floats the breath of the Divine! The modest church, peeping from the

branches, and over and above all loom the circling crests of the everlasting hills. Here

lies all that harmony and repose in nature, and that delightful grouping of wood, meadow,

river, lake, and mountain impregnated with the glamour of poetry and the charm of literary

association. Ruminating beneath the branches of an aged tree, we marvelled on the beauty

of the spot; sweetly on the ear came that bubble and even flow of water, and the distant

melody of cascades.

"No sound is uttered, but a deep

And solemn harmony pervades

The hollow vale from steep to steep,

And penetrates the glades."

The surrounding ranges of hills were sparkling with a lustre almost heavenly; here and there could be seen the twinkling lights of cottages, nested, as it were, in leafy bowers. A veil of mist gradually crept over the lake, from whence the splash of oars and the music of voices floated; the blackbird had ceased his warbling, and the cushats [pigeons] had fallen to slumber in the pine trees, bats whirled hither and thither as if in aimless flight; a buzz clock [flying beetle (?)] droned past, causing that peculiar, slumberous, dreamful sound. Thus musing, as the clock in the church tower chimed the hour of ten, we turned away with loftier feelings by this communion with nature around Rydal Mount.

"O vale and lake, within your

mountain urn,

Smiling so tranquilly, and set so deep !

Oft doth your dreamy loveliness return,

Colouring the tender shadows of my sleep

With light Elysian; for the hues that steep

Your shores in melting lustre, seem to float

On golden clouds from spirit lands remote,

Isles of the blest and in our memory keep,

Their place with holiest harmonies. Fair scene,

Most loved by evening and her dewy star,

0, ne'er may man, with touch unhallowed, jar

The perfect music of the charm serene !

Still, still unchanged, may one sweet region wear

Smiles that subdue the soul to love, and tears and prayer.

Mrs. Hemans.

Another poetess says :-

Thee, too, I found within thy sylvan dell,

Whose music thrilled my heart, when life was new,

Wordsworth ! 'mid cliff, and stream, and cultured rose,

In love with Nature's self, and she with thee.

Thy ready hand, that from the landscape cull'd

Its long familiar charms, nock, tree, and spire;

With kindness half paternal, leading on

My stranger footsteps through the garden walk,

'Mid shrubs and flowers that from thy planting grew;

The group of dear ones gathering round thy board,

She, the first friend, still as in youth beloved;

The daughter - sweet companion - sons mature,

And favourite grandchild, with its treasured phrase,

The evening lamp, that o'er thy silver locks

And ample brow fell fitfully, and touched

Thy lifted eye with earnestness of thought,

Are with me as a picture, ne'er to fade,

Till death shall darken all material things."

Mrs. Sigourney

*It was one of these Wythburn worthies who

had but two sermons, which he kept in a crevice near the pulpit. One Sunday he was

compelled to announce that as some mischievous "lads" had pushed the sermons so

far in as not to be got hold of, he would read them a lesson from Job instead, the first

two chapters of which were great favourites with the dalespeople.

§ EXTRACT FROM THE NOTE BOOK OF A TOURIST

WHO ARRIVED AT GRASMERE, JULY 21ST, 1827 :-

On entering the church, found the villagers strewing the floor with fresh rushes. Among

the seasons of periodical festivity at this place was the rush bearing, or the ceremony of

conveying fresh rushes to strew the floor of the parish church. This method of covering

floors was universal in houses, while floors were of earth, but is now confined to places

of worship. The bundles of the girls were adorned with wreaths of flowers, and the evening

concluded with a dance. In Westmoreland the custom has undergone a change. Billy

remembered when the lasses bore the rushes in the evening procession, and strewed the

floors at the same time that they decorated the church with garlands; now the rushes are

laid in the morning by the ringer and clerk, and no rushes are introduced in the evening

procession. I do not like the old customs to change; for, like mortals, they change before

they die altogether. Wordsworth is the chief supporter of these rustic ceremonies. The

procession over, the party adjourned to the ballroom, a hayloft at my worthy friend Mr.

Bell's, where the country lads and lasses tripped it merrily and heavily. They called the

amusement dancing, but I called it thumping, for he who could make the greatest noise

seemed to be esteemed the best dancer, and on the present occasion I think Mr. Pooley bore

away the palm. Billy Dawson, the fiddler, boasted to me of having been the officiating

minstrel at this ceremony for the last six and-forty years. He made grievous complaints of

the outlandish tunes which the "Union Band Chaps" introduced. In the procession

of this evening they annoyed Bill by playing the "Hunter Chorus is Friskits."

"Who" said Billy, "can keep time with such a queer thing?" Amongst the

gentlemen dancers was one Dan Burkitt; he introduced himself to me by seizing my coat

collar in a mode that would have given a Burlington Arcade lounger the hysterics, and

saying, "I'm old Dan Burkitt, of Wytheburn, sixty-six years old - not a better jigger

in Westmoreland." No, thought I, nor a greater toss pot [drinker]. On my relating

this to an old man present, he told me not to judge of Westmoreland manners by Dan's.

"For," said he, "you see, sir, he is a statesman, and has been at Lunnon

[London] and so takes liberties." In Westmoreland, farmers residing on their own

estate are called "statesmen." The dance was kept up till a quarter to twelve,

when a livery-servant entered, and delivered the following verbal message to Billy:

"Master's respects, and will thank you to lend him the fiddle-stick." Billy took

the hint; the Sabbath morning was at hand, and the pastor of the parish had adopted this

gentle mode of apprizing the assembled revellers that they ought to cease their revelry.

The servant departed with the fiddle-stick, the chandelier was removed, and when the

village clock struck twelve, not an individual was to be seen out of doors in the village.

No disturbance of any kind interrupted the dance. Dan Burkitt was the only person at all

"how came you so ?" and he was non se ipse [?] before the jollity

commenced. He told me he was "seldom sober," and I believed what he said. The

rush bearing is now, I believe, almost entirely confined to Westmoreland.

¶ Mrs. Hemans thus describes [her home] Dove's Nest:-"The house was originally meant for a small villa, though it has long passed into the hands of farmers, and there is, in consequence, an air of neglect about the little demesne, which does not at all approach desolation, and yet gives it something of touching interest. You see everywhere traces of love and care beginning to be effaced - rose trees spreading into wildness - laurels darkening the windows with too luxuriant branches; and I cannot help saying to myself, 'Perhaps some heart like my own in its feelings and sufferings has here sought refuge and repose.' The ground is laid out in rather an antiquated style, which, now that nature is beginning to claim it from art, I do not at all dislike. There is a little grassy terrace immediately under the window, descending to a small court, with a circular grass plot, on which grows one tall, white rose tree. You cannot imagine how much I delight in that fair, solitary, neglected-looking tree. I am writing to you from an old fashioned alcove in the little garden, round which the sweet briar and the rose tree have completely run wild; and I look down from it upon lovely Windermere, which seems at this moment even like another sky, so truly is every summer cloud and tint of azure pictured in its transparent mirror."

Edmund Bogg, Lakeland and Ribblesdale, 1898