CROSBY RAVENSWORTH.

The

village of Crosby Ravensworth is remarkably picturesque, being situated

near the junction of the stream from Odindale with the Lyvennet; these

streams afford marked features of natural beauties, and are enhanced by

the splendid sycamore trees in the neighbourhood of the Church and

Hall. It is also a very good specimen of villages arranged under the

feudal times, when the resident lord of the manor exercised an almost

despotic sway over the tenants and other inhabitants. The Hall,

therefore, as the manorial residence, would be a centre near which were

the dwellings of the villagers. One series of buildings is known as

Tenter Row; probably a corruption of The Enter Row, being at one

entrance of the village, and thus called in contradistinction to Low Row

at the other end. In these would live the tenants immediately dependent

on the Hall, while others, not so closely connected, resided further up

the village. There is the church also, impropriated to Whitby Abbey by

one of the earliest manorial lords. It is dedicated, according to Randal

Sanderson, to St. Lawrence; but Rev. Thomas Machell says it was

dedicated to St. Leonard. This latter might originate from that hospital

at York having lands here. There is a tradition of some religious

buildings having existed on the north side of the churchyard, and a

great portion of the land belonged; and from it must have originated the

names of Monks’ Barn, Monks’ Bridge and Monks’ Garth. Opposite the

church is the vicarage, a truly characteristic building; it has

undergone many alterations and additions under the late vicars, but is

especially indebted to Rev. G. F. Weston, who has enlarged and laid out

the grounds with admirable taste.

The

village of Crosby Ravensworth is remarkably picturesque, being situated

near the junction of the stream from Odindale with the Lyvennet; these

streams afford marked features of natural beauties, and are enhanced by

the splendid sycamore trees in the neighbourhood of the Church and

Hall. It is also a very good specimen of villages arranged under the

feudal times, when the resident lord of the manor exercised an almost

despotic sway over the tenants and other inhabitants. The Hall,

therefore, as the manorial residence, would be a centre near which were

the dwellings of the villagers. One series of buildings is known as

Tenter Row; probably a corruption of The Enter Row, being at one

entrance of the village, and thus called in contradistinction to Low Row

at the other end. In these would live the tenants immediately dependent

on the Hall, while others, not so closely connected, resided further up

the village. There is the church also, impropriated to Whitby Abbey by

one of the earliest manorial lords. It is dedicated, according to Randal

Sanderson, to St. Lawrence; but Rev. Thomas Machell says it was

dedicated to St. Leonard. This latter might originate from that hospital

at York having lands here. There is a tradition of some religious

buildings having existed on the north side of the churchyard, and a

great portion of the land belonged; and from it must have originated the

names of Monks’ Barn, Monks’ Bridge and Monks’ Garth. Opposite the

church is the vicarage, a truly characteristic building; it has

undergone many alterations and additions under the late vicars, but is

especially indebted to Rev. G. F. Weston, who has enlarged and laid out

the grounds with admirable taste.

BATTLING TREE, MONKS’ BRIDGE, VICARAGE AND SCHOOL.

There is the mill, where the tenants were required to grind their grain, subject to the lord’s moultre. The inn, too, opposite the church, is a genuine specimen of a village alehouse, with its sign of “The Rising Sun,” significant of the landlord’s good ale, “always rising never to set,” “cheering the heart it never saddens.”

Up the village is a large spring; near it stood an ancient elm tree, about which the lazy wives of the village gathered in groups to gossip on the characters of their absent neighbours. The well still flows as usual, but the picturesque old tree is gone; its place is, however, occupied by a young one planted by Mr. Weston.

Another rendezvous of the fair sex was the Battling Tree on the Low Green; but those frequenting this were of a more thrifty class; for on the butt of the tree they were in the habit of battling or beating their homespun webs after immersing them in the water.

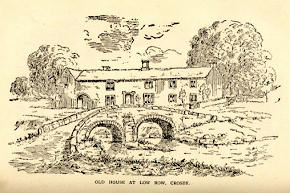

Near

the Battling Tree are the Butts, where the young men were wont to

practise archery and athletic games, such as running, wrestling,

throwing geayvelock, &c. They consist of two mounds about 100 yards

apart; upon these were erected temporary marks to shoot at. To the

practice on these butts we may attribute the skill of the yeomanry as

marksmen in times gone by. Every village green had its butts, and the

villagers were required by the lord of the manor to practise, so that

they might be able to contend with the Scots in case of an invasion, or

border foray. In some places the mounds have been levelled away but the

name still retained. They are to be found at Reagill near the school,

and also at Maulds Meaburn. Time, however, has made great

revolutions. These customs are now laid aside, being no longer required,

and the houses in which the actors dwelt have undergone alterations more

than once, especially Low Row, which was rebuilt in 1860, on the site of

the old house seen in the sketch. The previous house bears the date of

[ ]

Near

the Battling Tree are the Butts, where the young men were wont to

practise archery and athletic games, such as running, wrestling,

throwing geayvelock, &c. They consist of two mounds about 100 yards

apart; upon these were erected temporary marks to shoot at. To the

practice on these butts we may attribute the skill of the yeomanry as

marksmen in times gone by. Every village green had its butts, and the

villagers were required by the lord of the manor to practise, so that

they might be able to contend with the Scots in case of an invasion, or

border foray. In some places the mounds have been levelled away but the

name still retained. They are to be found at Reagill near the school,

and also at Maulds Meaburn. Time, however, has made great

revolutions. These customs are now laid aside, being no longer required,

and the houses in which the actors dwelt have undergone alterations more

than once, especially Low Row, which was rebuilt in 1860, on the site of

the old house seen in the sketch. The previous house bears the date of

[ ]

During his life he made himself a monument, unknown to himself – which will bear his name, for centuries perhaps – by planting a clump of trees on an elevated piece of ground on Meaburn Moor; a landmark to all the north of Westmorland, and known to every one as “Johnny Haa’ Trees.”